ANM: Fear of dying is perhaps the most defining feature of the human psyche; humanity is seemingly in equal parts fascinated and terrified by the notion of death. This fascination, I would propose, is natural and somewhat unavoidable. Fear, however, is not. Deeply ingrained into human consciousness is a perhaps unnecessary apprehension; is it possible that this fear, deep and complex as it undoubtedly is, is merely the result of an incorrect application of human reasoning to our natural instincts? It is true, of course, that we possess the instinct to survive, but perhaps the image of dying as a profoundly frightening process is one painted by an incorrect conclusion, a misinterpretation of our predisposition to strive for survival. Were this not the case, were humanity not shaped by this fear, the makeup of society would surely be vastly different. One need only take a passing glance at the nature of the world’s major religions, all of which provide some way around the finality of death, and some way in which a positive existence can be achieved after dying, or modern medicinal practices, which strive to postpone the death of each individual regardless of the effect on quality of life, to see the impact of this fear. Of course this question is only hypothetical, fear of death will always be a major feature of the past, but perhaps not the future. Perhaps the next step in human intellectual development involves relinquishing this fear, and dealing with whatever impact, positive or negative, that this would have on the nature of society.

JS: Could you explain a bit more about what exactly you mean by “a misinterpretation of our predisposition to strive for survival”? Whose misinterpretation? What is the misinterpretation? I think the fear of death is primordial and nearly unavoidable. The prospect of eternal nothingness is unfathomable, especially as we live longer and become so accustomed to, well, existing. There are no good metaphors for death. Sleep’s brother? Too easy. Dreamless sleep? Too comforting. I came up with one I rather like: Death is the tunnel at the end of the light. To rage against ‘the dying of the light’ (Dylan Thomas’ villanelle) seems perfectly acceptable, even rational, to me. I would love to give up that rage and that fear, but idea of nothingness is simply too horrifying. I don’t want to live forever. But neither do I want to die forever. What a dilemma!

ANM: What makes the idea of nothingness so horrifying? I do not deny that it is, aggressively so, but surely, in itself, it should be, well, nothing. Surely there is a man-made leap there, some kind of jump, the size and nature of which is perhaps more debatable, to a conclusion. This jump, I would argue, is the misinterpretation of our instincts; we naturally avoid dying, avoid the descent into nothingness, and have somehow reached the conclusion that that which we naturally avoid is to be feared. I take issue with this. We naturally avoid pain and, yes, it is unpleasant, but we do not hold towards it the same deep and complex fear as we do towards death. We strive for warmth and shelter, but the idea of the cold is not horrifying as such. The difference with death is that we have no reference point, we cannot experience mild death as we can experience mild cold or pain, and so we must make assumptions as to the extent of the displeasure of death. Our assumption, quite clearly, is that death, and therefore nothingness, is, again, horrifying. Perhaps this assumption is incorrect, and there is no need to fear nothingness. One would be hard pushed to describe exactly what about nothingness is frightening without constant reference to the absence of life, but of course in a state of nothingness this would not apply, nothing would. In short, nothingness in itself cannot be horrifying, and yet the idea of it is. This points to a mistaken interpretation of something along the path of human development surely. I would suggest that this ‘something’ is our instinct to survive. In terms of ‘Whose misinterpretation?’, I can offer no real answer, the proverbial first men perhaps? Can the nature of the collective human conscience by the individual minds of individuals at the beginning of human history? I suppose the most accurate answer possible is that the misinterpretation must predate any religious ideas concerning life after death, as this is surely a response to the fear, surely a hanging ladder offering an escape from the tunnel, as you say, at the end of the light.

JS: “In short, nothingness in itself cannot be horrifying, and yet the idea of it is.” I think this thought is precisely the case, and a kind of mortal world-thought that is the only case. I wonder if Lucretius long ago tried to sort this out by saying that it is irrational to fear death because we do not know what death is and if it is nothing than why get so worked up about it? It is the lead up to death that is so awful, as you suggest. The very idea of the big D. The panic that results. The sense of absurdity. Which makes Nietzsche’s aphorism so enchanting: “The thought of suicide gets one through many long nights.” What do you think of that thought?

ANM: Unique to human kind is the ability to recognise and identify things that we can never fully understand; perhaps the true cruelty of the human condition lies in the fact that we are aware of our own ignorance. Could this be the root of our troubled relationship with death? Is our inability to comprehend the notion of eternity, our inability to conceive of ourselves simply not existing, at the heart of our fear? Perhaps the feeling of helplessness and panic that results from this apparent ignorance is what is so horrifying. If this is the case, then perhaps ‘the thought of suicide’ can provide some strange comfort; perhaps the notion of taking one’s own life offers some remnants of control over the situation, some way that we, as humans, can at least interact with our own passing. But what, then, is the solution? Is there one? Must we come to accept our own ignorance, somehow come to terms with the fact that we don’t know, and never will know, anything substantial about the nature of death? This is not as simple as merely admitting to ourselves how little we know; we must cultivate true contentment with not knowing. If this is the solution, (and this is, of course, far from a final conclusion), then is it possible, and, if so, how can it be done?

JS: When Lord Byron’s daughter, Allegra did not live up to her name and died at five years old in an Italian convent, the father remarked, ‘Allegra has solved the riddle before us”. The only way to solve the riddle of death is to die and see if something happens next or if, in Emily Dickinson’s haunting phrase, “I could not see to see.” Byron tried to ‘cultivate true contentment with not knowing’, but he was too intelligent and self-aware to be sanguine about death. How can we imagine the future that does not include us? Don’t we persist as spectator, at some level, in this mortal fantasy? I think Freud said that we are all convinced of our immortality in our unconscious because we simply cannot think of ourselves as dead. And yet we know for certain that death is coming. Like a freight train. Or a chariot that swings low to scoop us up and take us to either Something or Nothing, probably the Latter. It is a fearful situation unless one believes in an afterlife and, even then, it could be that the afterlife is a terrifying cycle or some form of insanity. I rather doubt even the most pious Christian will suddenly sprout wings and a talent for the harp. And the lake of fire and all that hellish rubbish are clearly lies. What are we left with but anxiety and fear of the unknown and unknowable?

ANM: The only true function of fear and anxiety is prevention. But we cannot prevent death; our fear serves no purpose. Surely we should attempt, at some level, to relinquish this fear. I believe that this is possible. Actually, scratch that, it is not. Fear of ‘death’ will be a constant feature of humanity, it is unconquerable. But ‘death’ is imaginary, no one has ever been in a state of death, and no one ever will be; we live for a short time, we die, and then we cease to exist. Death is a word for the living, a reference point for those left behind to describe what they cannot comprehend. When we think of death, as if it is something that must happen to everyone, we are thinking of it as if we will experience it in some way, whether as ‘spectators’ as you say, or in the first person. But death is not something that happens to anyone, unless one believes in an afterlife, of course. We will not experience nothingness, we cannot, by definition. Surely then it is impossible for us to fear it in itself. I am not suggesting that we should look forward to nothingness, or embrace it with any great readiness, I merely believe that the panic and horror we experience around not existing is, when really thought about, somewhat ridiculous. Nothingness demands indifference. Yet the fear is undoubtedly there, as real and terrible as any other, more so in many ways. It follows therefore that we are attaching something else on to our view of nothingness, we seem to have tremendous emotional baggage around not existing. Why is this the case?

For one I would suggest that we are scared, and understandably so, of the process of dying; the pain we might experience, both physical and emotional, as well as the threat that the somewhat dormant fear of ‘death’ that we experience in everyday life will erupt as it moves closer. This is a scary thought; that in our last moments the fear of nothingness will truly conquer us, and we will go unwillingly. What are we left with for now then? Fear of fear itself? Its certainly not that simple. There is clearly something that we relate emotionally, and perhaps unnecessarily, to the loss of existence; something raw and tender, a sore spot in the human psyche. It is this, I believe, that, when uncovered, produces the horror and panic we associate with the fear of nothingness. Perhaps it is just ignorance, the fact is that we are so incapable of imagining not existing. Or perhaps intense sadness, grief for our lost consciousness, a sort of pre-emptive mourning for the loss of all that we have built while alive; our likes and dislikes, the relationships we’ve built, our own personal narratives to which we have become so attached, all of which will be lost to the world. Maybe, if this ‘sore spot’ is the problem, then it is different for every person. Perhaps this is why it is so hard to conquer. However hard and seemingly hopeless this conquering is, however, it is surely a worthy pursuit.

JS: I offer a poem by Philip Larkin because Alexander Pope was correct to refer to poetry as giving us ‘what oft was thought by ne’er so well expressed’.

Aubade I work all day, and get half-drunk at night. Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare. In time the curtain-edges will grow light. Till then I see what’s really always there: Unresting death, a whole day nearer now, Making all thought impossible but how And where and when I shall myself die. Arid interrogation: yet the dread Of dying, and being dead, Flashes afresh to hold and horrify. The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse —The good not done, the love not given, time Torn off unused—nor wretchedly because An only life can take so long to climb Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never; But at the total emptiness for ever, The sure extinction that we travel to And shall be lost in always. Not to be here, Not to be anywhere, And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true. This is a special way of being afraid No trick dispels. Religion used to try, That vast moth-eaten musical brocade Created to pretend we never die, And specious stuff that says No rational being Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing That this is what we fear—no sight, no sound, No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with, Nothing to love or link with, The anaesthetic from which none come round. And so it stays just on the edge of vision, A small unfocused blur, a standing chill That slows each impulse down to indecision. Most things may never happen: this one will, And realisation of it rages out In furnace-fear when we are caught without People or drink. Courage is no good: It means not scaring others. Being brave Lets no one off the grave. Death is no different whined at than withstood. Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape. It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know, Have always known, know that we can’t escape, Yet can’t accept. One side will have to go. Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring Intricate rented world begins to rouse. The sky is white as clay, with no sun. Work has to be done. Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

I think ‘not to be here / not to be anywhere’ is meant to echo Hamlet’s wistful ‘not to be’. I cannot get over death. I cannot get over ‘Aubade’. I will never understand how any thinking being, res cogitans, as Descartes said, can ever get over death except by committing what Camus called ‘philosophical suicide.’ Our dialogue is a ‘special way of being afraid,’ except that you are less afraid, it seems, than I am. Is that simply because you are several decades younger than me? I don’t think so. For I was exactly ten years old when Larkin’s poem, which I had not read (he had not written it yet, but that’s not the point) engraved itself on my young, sad, thoughtful, beautiful, blighted heart. I think some people have a predisposition to fear death. How one originates that predisposition seems to be what we are trying to discover. We are attempting to probe that sore spot you mentioned.

ANM: As much as I'd like to be, I don't think I'm any less afraid; if some people do have a predisposition to fear death, then I am certainly one of them. It is the extent of my fear that makes me so determined to find some solution, so determined that there must be some solution. I accept that I will never be indifferent to death, and certainly that I will never be anything approaching excited for it. I am willing to accept that there will always be anxiety, significant anxiety, around the ‘unknown and unknowable’, and the clearly daunting idea of not existing. I am not, however, willing to accept the desperate panic and horror that arises whenever I go to deeply into the subject. Surely it is possible, at the very least, to lessen this reaction. I hope that probing the sore spot, truly investigating its roots and its nature, I can come to understand it and, eventually, soften it.

I think the best explanation of the sore spot I can offer for now is some curious mix of frustration with ignorance and intense sadness. I have suggested that the solution is to ‘cultivate true contentment with not knowing’, but I think we both know that doesn't quite cut it; it seems so counterintuitive to accept ignorance, this would surely be fighting the development of the human intellect, rather than furthering it. It seems therefore that the only viable solution is to try to conquer the great sadness we feel around dying. Perhaps we must learn to become less attached to our own lives. This sound strange but I think that, unless we can become less invested in our own narratives, and come to see our own existence as part of something larger, then horror and panic around dying may be inevitable. Who wants to see their favourite story end? Must we learn to see ourselves merely as part of the great story, rather than seeing it as beginning and ending with our own lives?

JS: I would love to see myself as part of ‘the great story’ so long as that story is not a universe that is being torn apart by dark energy and that is expanding—gods knows how—at an accelerating rate. That particular great story tends to intensify the absurdity of human existence, so far as I am concerned. But I know others who are actually comforted, even amused, by the vastness of space and the certainty of our future oblivion as individuals and as a species. But what if there is a way of surviving physical death that nevertheless has absolutely no relation to any philosophy or religion so far invented? What if we grow particular ‘souls’ (it must be a metaphor) that go beyond synapses and electro-chemical secretions in the brain? Have you ever wondered if the intensity of wondering has a residue or afterlife that in no way resembles the garden variety of afterlives that world religions have vended to us? We solve Byron’s riddle when we die as some ‘part’ (another metaphor) of us joins a greater story (all verbs and nouns are metaphors at this point) that makes the Big Bang and dark energy look like stale porridge. I hasten to add that I do not believe that this afterlife has anything at all to do with ‘consciousness’ as we have so far conceived it. If this little soulful hunch of mine is a delusion bred of fear—and it probably is—then I am simply spinning my mental wheels and trying like hell to avoid the harrowing probability that death is precisely Larkin’s ‘anaesthetic from which none come round’. My fanciful notion is no doubt my attempt to think outside the coffin. But, as you suggest, one must do something.

ANM: The inevitable destruction of our universe is not an easy notion to sit with. I suppose, on the surface, it does wipe away any meaning from the ‘great story’ with which we so wish to engage. However, the eventual demise of the entire world is no different, in terms of our ability to transfer meaning from our own lives onto the lives of those who outlive us, to the eventual demise of any one individual. We can still play active and valuable roles in a story that will carry on for generations after we die. We should consider ourselves lucky; it is those who will live mere decades before the apocalypse who will face the true existential crises.

I wonder if we are, perhaps, overly pessimistic in our pre-emptive acceptance of eternal nothingness. After all, we have to question our philosophy if ‘thinking outside the coffin’ begins to take on negative connotations. If little hunches such as yours occur, they should surely be nourished and investigated, followed through to the furthest extent possible. The problem I have always had with this issue I that I have no hunch. Unfortunately, the idea that reverberates loudest around my mind is that of eternal nothingness. I’d love for this not to be the case and, failing finding some acceptance of this notion, I hope that it is one day not the case. I’d like to have some idea of an alternative to oblivion, one that I can, if not wholeheartedly believe in, then at least entertain the possibility of. I’d like to know more about yours. What do you mean by the ‘residue or afterlife’ caused in some way by wondering? How does this come about, and how would we, whether conscious or not, interact with it?

JS: I use old words like ‘residue’ and ‘afterlife’ because I have not yet invented fresh metaphors for the fledgling, idiosyncratic soul I have imagined. Nietzsche was right to observe that most of our concepts are shot through with metaphor, including the verbs—shot through—that we use to put them into action. Here is a rather undistinguished poem I wrote many years ago when I learnt that the great Goethe’s dying words were, apparently, ‘more light!’ I have spent most of my life trying to get my modest brain around the shocking fact that hugely-developed brains can go from being to nothingness in a single second.

More light!

More light! cried Goethe

pushing darkness away--

He could not see to see

nor cease to cease.

fiat lux!

fiat logos!

fiat tenebrosus!

The memory-hoard dies

there on the sad height,

and so lucid, dying Goethe

drawing his last breath,

cried out, more light!

and was great with death.

Not much consolation here. No residue. Sad as a Larkin. But dead honest. Does that ‘count’ for something? Who can decide that?

ANM: The more I consider this topic, the more I feel that the success of one’s relationship with dying, and the notion of death, is defined by their last moments; the moments which they know that death is coming, and are forced to confront the implications head on. If, in my last moments, I am filled with acceptance and contentment, perhaps even vague excitement, then I will consider my relationship with death a successful; the time I had spent pondering the subject, attempting the soften the fear, will have been worth it. The sore spot successfully soothed. If, on the other hand, fear is the overriding emotion, I will have failed. In this case, I suppose, honesty ‘counts’ for everything. A life lived in false acceptance and optimism will surely end in fear. The nature of the fear is important here; there will no doubt be anxiety in our last moments, but panic is not necessary.

‘More light!’. But we will not live in darkness, surely this is one thing of which we can be sure. If nothingness truly is our ultimate fate, then upon our entrance into oblivion light and dark will simply cease to be. This is where the fear lies, I believe; in attributing empirical notions to our descriptions of the unknowable, and insensible.

The instantaneous change from complexity to nothingness is a notion that I must admit I find terrifying. But why? It seems to achingly sad, seems render everything pointless. Sad isn’t the word, I don’t think, its more complicated than that. What, then, is the word, and how do we conquer it?

JS: The word ‘absurdity’ comes to my mind. An enormous ‘what’s the point’ hovers over our lives. We have art, as Nietzsche observes, so that ‘we may not die of the truth’. That truth is the truth of the total absurdity of human existence. So what do we make of this line of poetry: “Death is the mother of beauty” (Wallace Stevens, ‘Sunday Morning’). Is everything, every sad little pansy, every curve of a feminine jawline, every swirling bit of stardust more beautiful because we are doomed? I would like to believe that but the loss of future consciousness sort of ruins everything for me. I have no idea how to ‘live in the moment’ and the dispensations of ‘carpe diem’ are thus unavailing. Perhaps it’s time to give abstruse Heidegger a bit of attention. His idea of an authentic ‘being-towards-death’ suggests that the only proper relation to finitude is a healthy anxiety about it, in which case our very dialogue is an activity he would warmly applaud. Avoiding the question of mortality is the work of a cowardly, inauthentic human being. Our being is wrapped up in time and time is finite, full stop (so to speak). For Heidegger, then, ‘being-towards-death’ is the mother of a kind of beautiful anxiety and courageous self-awareness. Hamlet’s mortal anxieties crystallise such self-awareness and that is why I am so mesmerised by the melancholy prince. Again, I want to believe what Heidegger says is true, but I am simply not capable of a beautiful or healthy anxiety about death, as you can tell from my remarks and thoughts. So I come back to art as the ONLY way out. The only time I forget about death is when I am so immersed in a work of art—reading one or especially trying to produce something worthy myself—that I forget to breathe, I forget to think about death, I forget everything but the intellectual and sensual pleasure of consuming the sculpted sufferings of a magnificent genius. That is art that keeps us from dying of the truth. It does not last very long but the diversion is substantial. Making love, playing tennis and watching dolphins disporting in the swelling sea are also lovely diversions but not so reliably entrancing as being lost in Lolita or Ulysses or Bach’s Mass in B Minor or Van Gogh’s field of crows. Does this make any sense or am I deluding myself once again?

ANM: I think this is as close as one can come to defining the purpose of humanity, with respect to our relationship with dying; finding the balance between distracting ourselves, and this ‘healthy anxiety’. A life lived without distractions, without art (as the most complex and rewarding) , or without any of the other kind of pleasures you mentioned, would be miserable no doubt, regardless of the intense and potentially ground-breaking philosophical breakthroughs one might make throughout the course of a life dedicated to internal death dialectic. And, as we have already mentioned, a life throughout which the notion of dying was ignored, simply pushed below the surface in pursuit of a more pleasurable existence, would surely end in overwhelming fear. A balance therefore is necessary. The notion of dying must always be on our horizon, but must never dominate our view. A ‘healthy anxiety’ is perhaps the end result, but I think a healthy curiosity must be the starting point. Every time the fear surfaces, it is perhaps necessary to investigate it, ask why it is there; attempt to break the fear of dying into its individual components. ‘What am I really afraid of? Nothingness? I can’t be. Loss? I won’t feel it. That seems to be what we are doing here; investigating, interrogating even, our fear. And, while I cannot begin to pretend that I have overcome my anxiety around dying, I can say that, so far, it has helped. The fear of death, it would seem, is truly greater than the sum of its parts. Through continuing to isolate and identify these parts, as we have done in parts earlier in our discussion, I believe that we can lessen the fear.

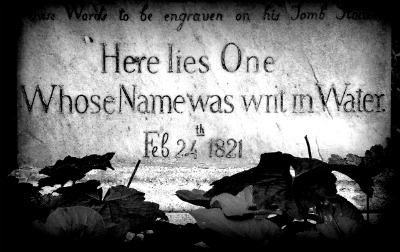

JS: Perhaps the prospect of certain death double-helixes fear and fascination. Larkin’s ‘Aubade’ unflinchingly detects the DNA of dread. I think our dialogue is both fearful and fascinated. Does fascination lessen fear or serve to deepen it? Does analysis of the kind we are attempting make us better, happier or healthier animals? I wonder if porpoises or whales or silverback apes ever think about death? Is my curiosity about such matters unhealthy to the extent that it makes me too preoccupied for my own good—or anyone else’s good. I used to drive my father a bit mad with these questions when I was about sixteen. I suppose my greatest worry about death is that it looks like the death of the very conditions of possibility of curiosity, the implosion of curiosity, the end of wonder itself. In other words: the end of the dialogue. Our dialogue will persist as a document, it is true, but how can that give me any comfort or consolation? I am reminded of the most honest and moving epitaph I know, composed by John Keats for his own gravestone.

ANM: I think the power of our fascination, if harnessed correctly, can serve to lessen our fear. Perhaps deepening the fear is a necessary part of the path to lessening it; we must truly engage with our fear in order to understand it, and understanding it is surely our only hope of taming it. I think that’s what we’ve done here: formally engaged with the fear of death. This isn’t easy, nor entirely pleasant at first; its far easier to either push it away, or accept that it is present and volatile and attempt to distract ourselves from it. But this is the decision we’ve made in entering into this discussion: that it is better to confront our fear in the process of embracing our fascination, rather than suppress our fascination on the process of avoiding fear. I cannot say with any kind of authority that this is the correct decision. As I have said before, however, if I live my last moments in fear I will consider it a failure, and I truly believe that the option we have chosen through this dialogue is the best way of avoiding that. Through investigation we will hopefully understand, and through understanding we will, perhaps, begin to conquer.

‘The implosion of curiosity’ is precisely the kind of notion that needs to be explored. It is a terrifying and extremely saddening thought. Again we must ask, why? Sadness is understandable, inevitable even, but terror is surely not. Our fear on this subject seems to come from our simultaneous ability and inability to comprehend the notion of death; we are able to think about it, but only in terms of the living world, always with some reference to our own consciousness. As we have previously established, this is a fundamentally incorrect conception. An even vaguely happy person could never be expected to feel no sadness around losing their life, and anxiety is understandable as well, but fear of death, panic and terror on the scale that we have discussed, is an unnecessary product the human consciousness, and one that we should work, or should I say, continue to work, to dispel.

JS: The only thing—for me—that dispels the fear of death, even for the flicker of a moment, is our dialogue, which is a diverting, lively, lovely form of curiosity. The rest, as Hamlet says, is silence.