MMH: Spinoza was, on all surviving accounts, a good – if unexceptional – optician, a better maker of lenses than he was a theorist of them. The lens and its trickery are slightly thorny for empiricism at large: at once revelatory and deceptive. The lens puts all too sharply in focus the intervention of the body in perception. It is unsurprising then, if we grant a little psychoanalytic license, that Spinoza emerges as one of philosophy’s great elevators of the body. Spinoza – alongside Nietzsche, Bergson, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze (and Guattari) – is keen to disabuse us of any fantasy of the mind’s sovereignty – to stick our heads firmly back on our torsos. In particular, Spinoza the optician is under no illusions as to the causal relationship between mind and body; no object or concept registered by the senses has not already been physically secured and mediated by the body. But the lens does not only reveal to us the mechanical underpinnings of sense data, it also imperils the sovereignty of our inspection – muddies the freedom of the voyeur.

Like Hegel, Spinoza threatens to make freedom a redundant category. If increasing our power to act is really identical to aligning our will with an inescapable chain of causation, why bother to retain the comforting name of action. Hegel’s similar bait-and-switch is found in Elements of the Philosophy of Right, where meaningful freedom produces actions perfectly harmonious with and conducive to the laws and ends of the state. While Hegel seems primarily interested in neutralizing ‘freedom’ as a political weapon against his utopian state, Spinoza’s interest in making himself and his fellow thinkers free appears sincere. Our unhappy optician cannot doubt that the mind depends upon the body, but is not so much a determinist that he will give up the autonomy of mind altogether. Action still lurks somewhere in the swill of reaction but can give up no ground to contingency. Nietzsche resolved a similar problem with something of a fudge. In the emblem of a dice-throw he marries contingency and necessity, and warns us that scientists have spent far too long looking at reactions without wondering what forces everything is busy reacting to.

It is somewhat unclear whether Spinoza thinks we ever really act at all. In passages it seems clear enough that as parts of nature we are beholden to its laws, causes, and affects, but Spinoza is also focused on ways in which we can reduce the sway of affects and increase our power to act. To be disentangled from at least some particles of God's extension and to retreat into ourselves. A metaphysical thread seems to sustain Spinoza in the midst of his potential contradictions: necessary action, willed determinism. It is under the shelter of God’s attributes that we retain the possibility of elevation, not by overturning physical causation but by becoming wilfully embedded in it – by, to borrow Nietzsche’s phrase, throwing off ressentiment. And who is he who goes on resenting necessity, who cannot help but try to make the ignorant see more clearly?

Spinoza philosophizes against fear, most of all, against the fear which proceeds from apparent indeterminacy, and against the futile striving that accompanies that belief in indeterminacy. This said, he is not against striving, what are we to make of the Ethics’ concluding remarks on the difficulty of dissolving oneself into the course of necessity and reaction? The split is not as easy as physical reaction, metaphysical action. The striving we should be doing has everything to do with seeing things properly, and who better than a lensmaker to know that seeing properly is a physical operation: a clearing of obstacles, a bringing into focus. What clings to me is the sense – amidst all Spinoza’s clarity, his endless ‘no doubt’s and Q.E.D.s – of almostness in the Ethics, of peeking between your fingers or squinting through your glasses. Look at the world, but only as much as you need to succumb to it. Understand reaction and the determinism of natural laws as abstractly as you can; walk backwards with your eyes closed into God’s embrace, but get a glimpse because you cannot help it. One of Borges’s sonnets for Spinoza pictures the philosopher dreaming up a clear labyrinth, and as he does so the ‘hands and space of hyacinth…almost do not exist’ for him.

Spinoza Las traslúcidas manos del judío Labran en la penumbra los cristales Y la tarde que muere es miedo y frío. (Las tardes a las tardes son iguales.) Las manos y el espacio de jacinto Que palidece en el confín del Ghetto Casi no existen para el hombre quieto Que está soñando un claro laberinto. No lo turba la fama, ese reflejo De sueños en el sueño de otro espejo, Ni el temeroso amor de las doncellas. Libre de la metáfora y del mito Labra un arduo cristal: el infinito Mapa de Aquél que es todas Sus estrellas.

CH:

There have been courtier philosophers, lens-grinding philosophers, and even engineer and strategist philosophers; but no philosopher, so far as I know, was a wholesaler or storekeeper.

—Primo Levi

Is Dr Levi telling the truth? Lens-grinding is long work. Squinting eyes, polishing round and round—it’s the kind of thing to make the memory of one’s body seem like a bad dream. One could sit there forever, imagining the perfect lens; there’s no such thing as a perfect lens. Only narrowing degrees of almost—and even the ideal is prone to aberration; beyond a certain level of resolution you need, yes, espejos. Or perhaps the only perfect lens is in the mind’s eye:

I say expressly that the mind has not an adequate but only a confused knowledge of itself, of its own body, and of external bodies, so long as it perceives things from the common order of nature, that is, so long as it is determined externally, from fortuitous encounters with things, to regard his or that, and not so long as it is determined internally, from the fact that it regards a number of things at once, to understand their agreements, differences, and oppositions. For so often as it is disposed internally, in this or another way, then it regards things clearly and distinctly, as I shall show below.

(Ethica II.29S; here and after tr. Curley)

So is it not ironic that the outcome of Spinoza’s toil should be a tool of physical enquiry? What had Spinoza in common with his fellow lens-grinder William Herschel, beyond that they both, in a sense, had their head in the stars? The former did not live out his ideal of an elevated body, if he had one. I think Freud would see in his hazy philosophizing afternoons another same-old body-denier, and from the poring-over (anality) of the glass-worker a familiar echo in the pedantry of his thought. I do not feel Spinoza’s philosophy; do you1?

Our body, to Spinoza, is out of our control (including the tongue—see the long scholium to III.2—and one wonders about the hands engaged in dialogue, or demonstrating ethics in geometric order) and yet we act. This is the funny action of the one whose freedom is sublimated into the One free cause; for whom to act is not as opposed to be compelled, but as opposed to feel passion. Is there a paradox? Yes, we are muddled by language—his passion is not the same as de Botton’s—as indeed though desire is man’s very essence could be lifted from the Analyst, Spinoza does not, I think, mean the same.

But you’re right; it would be dishonest to claim Spinoza does not elevate the body (Corpus; a sturdy dun-clothed body from a Rembrandt; a nation of storekeepers), in some regard. I needn’t direct you to these turns in his labyrinth of meditation:

The mind does not know itself, except insofar as it perceives the affections of the body

(Ethica, II.23)

The idea of any thing that increases or diminishes, aids or restrains, our body’s power of acting, increases or diminishes, aids or restrains, our mind’s power of thinking.

(Ethica, III.11)

So perhaps it’s the paradox of Spinoza that this doctrine should come from such a man in such utterly cerebral terms. May we affirm the body by means of algebra? Is it that very discord—warm-bloodedness in the language of Euclid and Descartes—which lends the glimpsing quality on which you almost put a clockwork finger? We know his menagerie of toy affects don’t really rain down from the laws of nature and nature’s God. In their uncanny precision do Spinoza’s propositions cross the horseshoe into a kind of poetry—a negative capability where contradiction is everywhere and nowhere and impossible to grasp?

From what has been said it is clear we are driven about in many ways by external causes, and that, like waves on the sea, driven by contrary winds, we toss about, not knowing out outcome or fate.

(from Ethica III.59S)

MMH: I think my alertness to the corporeality of Spinoza’s philosophy is probably the result of Deleuze’s Spinoza: Practical Philosophy. The book’s project is to draw lines between Spinoza’s Ethics and Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil; it dwells at length on Spinoza’s notion of agreement between natures as a substitute for moral thought. In particular, Deleuze is captivated by the analogy with bodies: what nourishes the body is good, what poisons it is bad – no more, no less. Deleuze sees in this pragmatism a disavowal of transcendent morality, and the ascendence of a philosophy which treats the mind (and whatever remains of the soul) more like the body. Then again, we might do well to recall what Deleuze said about his writings on the history of philosophy:

But, above all, my way of coping at that time was, I am inclined to believe, to conceive of the history of philosophy as a sort of buggery or, which amounts to the same thing, a sort of immaculate conception. I imagined myself as arriving in the back of an author and giving him a child, which would be his and which nevertheless would be monstruous.

Spinoza’s parallelism demands that we free our bodies alongside our minds, but again we run into an awkward kind of freedom. The body is liberated, to do what exactly? Here Deleuze fails us, fixated as he is on Spinoza’s joy-seeking, by ignoring all the prohibitions which bound Spinozist freedom. Crudely put, if there is to be no feasting, drinking, or fucking (if all these are really just kinds of affective slavery) – what do we do with the power to act physically? It is difficult to feel Spinoza’s philosophy not – it seems to me – because the philosopher himself is by nature too cerebral but because it is difficult to conceive of a corporeal philosophy free from appetites. Freud could not help but call Spinoza a tired body-denier, for Freud the body is only ever a constellation of desires and evasive satiations. As hard as Deleuze tries to unite Spinoza’s ethics with Nietzsche’s master morality, the Ethics has little time for the pleasures of hearty indulgence. All the same, perhaps we would do well to notice Spinoza’s refusal to denounce the body, when it would be all too convenient for him to do so. Minds, he reminds us, are no less prone to sickness, nor better wellsprings of action. If we take Spinoza’s parallelism seriously, what do we imagine to be the bodily correlate of the properly composed and clearly seeing mind? It is not – as might be lazily said for plenty of other revivers of bodies – a dance. Is it total stasis, a brisk but un-instrumental walk, or labouring over tough glass? We might simply not yet know, as Spinoza’s famous declaration suggests, what the body would get up to if liberated from its sad passions.

However, no one has hitherto laid down the limits to the powers of the body, that is, no one has as yet been taught by experience what the body can accomplish solely by the laws of nature, in so far as she is regarded as extension.

(from Ethica, III.2S)

I’m always a little hesitant to drift into reading as poetry what has meant, and might fail, to compose a system. Certainly, Spinoza can hear the knocking of contradiction as he works. His correspondence with the insistent and Socratic Blyenburgh, who – it might interest Levi to discover – was none other than a grain broker, reveals an urgent anxiety about patching up holes and smoothing over edges in the Ethics. Spinoza’s letter of 28th January 1665 busies itself with rescuing both his and Descartes’ conceptions of freedom from contradiction with the philosophers’ determinism.

Secondly: that our freedom is not placed in a certain contingency nor in a certain indifference, but in the method of affirmation or denial; so that, in proportion as we are less indifferent in affirmation or denial, so are we more free. For instance, if the nature of God be known to us, it follows as necessarily from our nature to affirm God exists, as from the nature of a triangle it follows, that the three angles are equal to two right angles; we are never more free, than when we affirm a thing in this way. As this necessity is nothing else but the decree of God (as I have clearly shown in my appendix), we may hence, after a fashion, understand how we act freely and are the cause of our action, though all the time we are acting necessarily and according to the decree of God.

(from Epist. 34 to Blyenbergh)

Spinoza’s marriages of contradictions do not read for me as poetic, but as architectural or geometric. Determinism and freedom need not collide or collapse but can rather be nested. They persist on different planes, and at different scales, separated by category. Freedom survives unscathed but cannot – ‘obviously cannot’ we can hear Spinoza saying – defy the law and logic of the structure within which it sits. Are these merely tricks of perspective – magnifications and reductions to clarify the labyrinth – or does Spinoza’s edifice hold up to tactile scrutiny: can we, bodies and all, live in the maze? Does the little room for decision, where man retains his capacity to affirm or deny fate, to tether his will to his understanding (or let it outstrip it in ignorant passion) persist of collapse in on itself, a trick of the light?

If there are slips, in Spinoza’s writing, into a poetry of contradictions they are to be found where his tone – so often gentle, reserved, or clinical – betrays him and runs loose. In a later letter to Blyenbergh, as Spinoza seems to lose his composure and his ethical mooring:

So anyone who clearly saw that, by committing crimes, he would enjoy a really more perfect and better life and existence, than he could attain by the practice of virtue, would be foolish if he did not act on his convictions. For, with such a perverse human nature as his, crime would become virtue.

(from Epist. 36 to Blyenbergh)

On what grounds is this virtuous criminal perverse? A tongue out of control indeed – we are no longer doing geometry.

CH: Wait a minute:

To use things, therefore, and take pleasure in them as far as possible—not, of course, to the point where we are disgusted with them, for there is no pleasure in that—this is the part of a wise man. It is the part of a wise man, I say, to refresh and restore himself in moderation with pleasant food and drink, with scents, with the beauty of green plants, with decoration, music, sports, the theatre, and other things of this kind […]

(from Ethica IV.45C1)

Remember also the phrase in big letters on the back of the Penguin: joy is a man’s passage from a lesser to a greater perfection. Though we may be in bond to the affects, they are not only our keepers. And if we consider pleasure as being, well,

The affect of joy which is related to the mind and body at once I call pleasure [titillatio] or cheerfulness [hilaritas]

(from Ethica III.11S)

—or perhaps you want to render laetitia (here, joy) as pleasure anyway—then insofar as experience from the world can lead to perfection or power or understanding, it’s such passions as pleasure, love (and not just love of God but any old love) that do it. Spinoza is not averse to hedonism, albeit a world-wise, moderated hedonism; one which recognizes that too much of a pleasure in imbalance will only make us miserable in the long run. One which has more time for the green plants than for the orgy—but avoiding misery is still the point.

You hit on something important when you identify that re-ascription to the mind of those things which would otherwise be considered caprices of the body or ways in which the mind is kept beholden to the body. Desire and appetite are affects of the mind, so denouncing the body for their sake hardly gets us anywhere. The way out is to force discipline (understanding) on our own mind. Indeed in Freud the psyche, not the body, is a patchwork of desires. The mind is more than the capacity for ratiocination.

Beyond this I’m not sure there is substance to the parallel. Body and mind are man considered now under the attribute of extension, now of thought—but there is no effort to pair off modes of extension with modes of thought, so to find the bodily correlate of thinking clearly (which is nothing but a mode of thought) is not a question with a straight answer. Yet I want to say that a body preserving itself is analogous to a mind understanding—insofar as to preserve itself is the very essence of a physical thing, and understanding (or more properly, desiring to understand) is the very essence of a mind.

Spinoza clearly found something in his life that was conducive to understanding—just as Freud found the cure to his own neuroses in that funny anthropomorphic thinking-chair, walled in with old books. Freud, by his own standard, was as much of a body-denier as Spinoza. One wonders how much of Nietzsche’s life was really occupied in dancing.

We do not free our bodies as we free our minds because extended things are determined by the laws of nature whereas thinking things are free insofar as they act. Man is determined insofar as he has a body but has the capacity to be free insofar as he has a mind. Only God is free insofar as He is undetermined. Thus the nesting of freedom and determinism, in that freedom and determination are properties of a thinking thing and an extended thing respectively, and those attributes have nothing in common. In this particular case the contradiction that concerns me is not between freedom and determination but between the implied dualism and the doctrine of one substance. One substance under two attributes—why not a pair of substances?

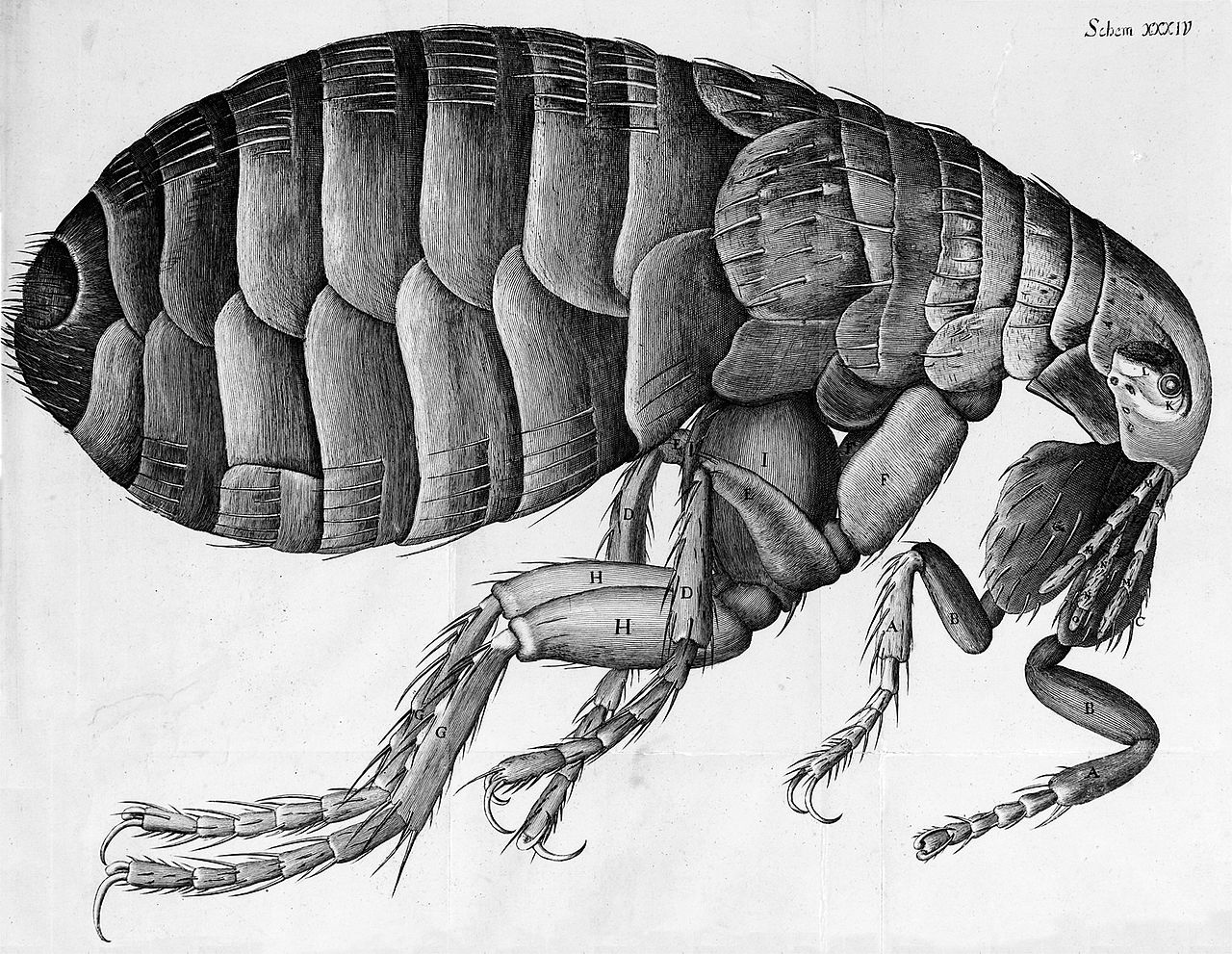

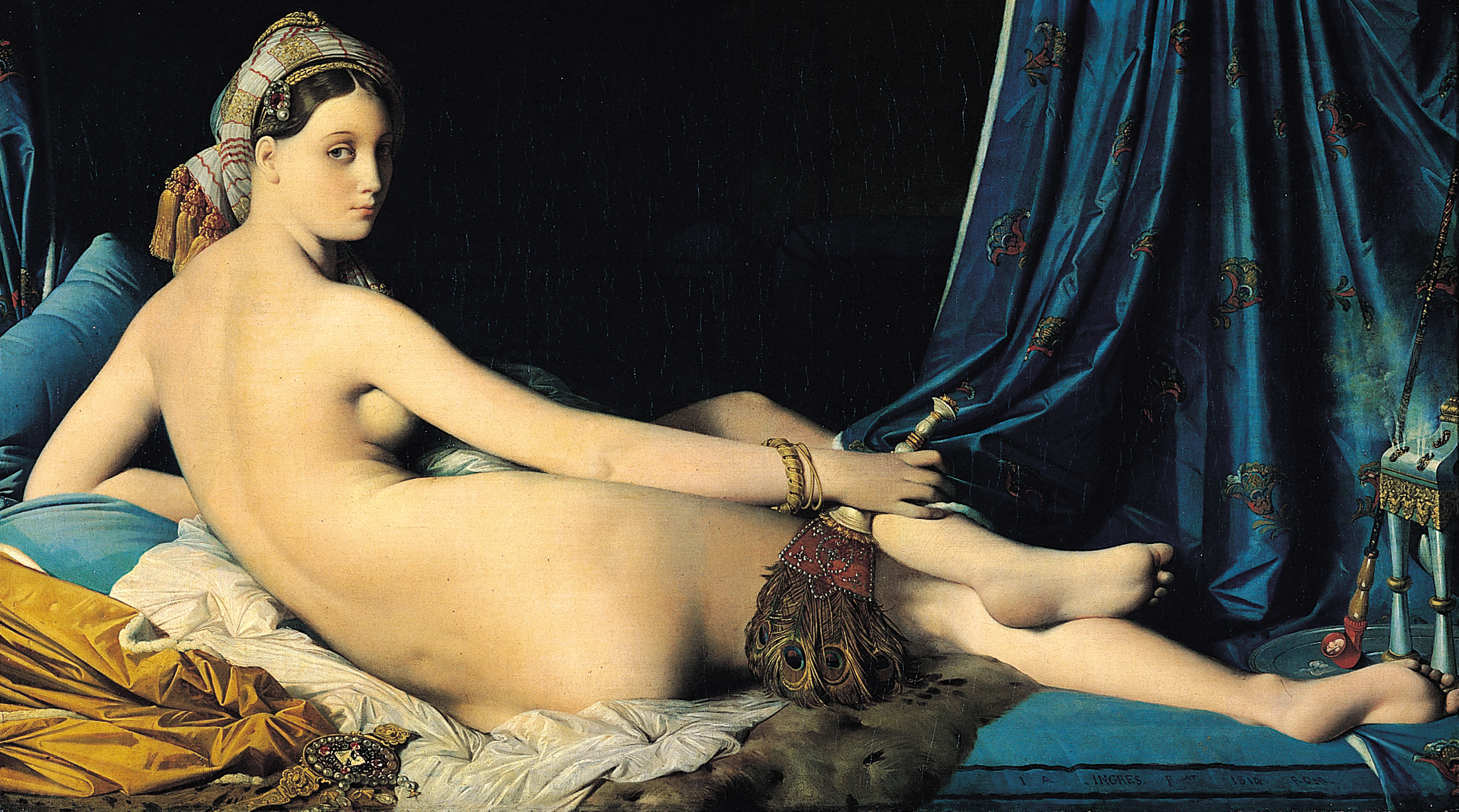

Poetry is the sort of word one regrets as soon as it’s put to paper—but let me say there is reading as poetry and appreciating as poetry, where by poetry I might understand a precise obliqueness to the truth. Thus poetry might be accidental and even pitiful if a precise statement of the truth was intended. It is a quality I find in this image, insofar as we realize the limits to its scientific veracity—

—and perhaps more loosely in that painting you showed me with the too-many vertebrae. If we do not appreciate Spinoza as poetry, then as what? Is there an appreciation of pity for the vision of the architect whose great cathedrals fall down?

Pity, in a man who lives according to the guidance of reason, is evil of itself and useless.

(Ethica IV.40)

Would Spinoza really explain away his slips as the work of an errant, bodily hand? Are the Ethics not to be considered as a product of Baruch de Spinoza wholly insofar as he was a singular thinking thing? Are the causes of the apparent misfires not to be founded lurking deep in his definitions—in your case in that he was a total pragmatist when it came to virtue? If not thought, then under what attribute must we consider the philosopher breaking vanishingly out of his own beautifully-wrought cage? Extension, for me, doesn’t quite cut it. Whatever the answer, it must be one in which freedom is a meaningful category.

MMH: How does a single substance retain its unity while obeying different laws under different attributes? As you suggest this element of Spinoza’s system is both a solution and a problem. Still, I am not quite sure that Spinoza is altogether on board with a clean split between an active mind and a reactive body, even if it is the most coherent reading of his philosophy. The mind is at least subdivided further, into one part which is at least as subject to laws of natural causation as the body, and another which can marshal this first part. Do these both act or react under the attribute of thought? And why – if what you intend is a tactical retreat from agency over the body in the wider war on affect – would you so strongly invite contemplation of the undiscovered capacities of the body? Even if thought is the vehicle of understanding, it is clear that it is ultimately the body itself which does the accomplishing of new actions.

Aside from this ambiguous declaration, Spinoza seems alert to the ways in which free thought can transform the sense of actions, even as the action remains determined. The responses to Blyenbergh spend much time trying to devise a solution to the problem of evil. Given his determinism, Spinoza avoids a strictly act-based ethics in favour of an ‘evil’ which emerges from the attitude of thought towards action. Thus, says Spinoza, Nero’s matricide is evil and Orestes’ is at least less so, not because of a difference between their acts (which do not alone have a moral character) but because of the relation of their free thoughts to these acts.

What, then, was Nero’s knavery? Nothing but this: he showed by that act that he was ungrateful, without compassion, and disobedient. God was not the cause of this, but was the cause of Nero's act and intention.

Here we run headlong into a problem again. If matter remains a strictly determined affair, including the matter of our tongues, how are we supposed to discover or intuit the thoughts of any other mind – the province of their freedom and therefore their evil? Evil surely dissolves into the unknowable, becomes a property of mental acts which can find no expression. In short, Spinoza’s determinism leaves no room for Nero to show anything of his thought by way of his action. You are right that the impulse which has Spinoza still denounce Nero’s knavery is not a slip of the hand, but I cannot tell whether it is an escape from his cage which he – under the attribute of thought – wants to make. Are we to take speech and writing as always and entirely physical phenomena?

What to do with the ruins of a cathedral is harder to say. Crumbling is a real problem for Spinoza, indeed it is more or less the definition of a bad thing: acts are bad when they decompose relations, good when they agree with the relations they come into contact with. I suspect Spinoza would want the crumbling cathedral fixed or forgotten, neither of which I feel able to do. As for poetry, insofar as Spinoza’s system crumbles in on itself, I am not sure its obliqueness to truth is precise in quite the way your fetching flea is. For one thing, I’m not confident enough of the truth in Spinoza’s case to say what has charmingly missed it. Appropriately, Spinoza’s system consists of elements in motion and elements at rest, it is too alive to be embalmed like the anatomically curious flea or the Grande Odalisque.

The Grande Odalisque is the apotheosis of orientalist exoticism, an erotic subject so sinuous and otherworldly that she even lacks a human spine. The picture’s obliqueness to anatomical reality is on some level a pragmatic one, an incoherency with purpose. Perhaps we can read a similar kind of instrumental incoherence in some of Spinoza’s apparent contradictions. We can know what he is getting at, and even appreciate the cleverness at work, with his account of Nero’s ‘knavery’, even as we doubt its soundness as a philosophical solution. Similarly, something is said – I agree under a different attribute to that which builds watertight systems – when Spinoza insists on the unity of substance, even if what is said or gestured at in this insistence struggles for translation. What is the point, then, of Spinoza’s insistence upon a single substance? There is an immediate syllogistic point in proving Spinoza’s kind of God. But there is also something faintly phenomenological – I think – in referring to a single substance rather than several – this being the change of perspective in which Deleuze finds Spinoza’s radical affirmation of life. To divide those things which are continuous in life – thought, extension – is to play the wrong kind of God, and to do bad metaphysics. To divide into separate substances that which must be unified by living in the world is to imagine oneself as God the sentient onlooker, whom Spinoza seeks to banish.

CH: Extension and thought are ways of seeing the same thing; the one substance, God, the world. There are no mental or physical acts, merely the same phenomenon seen now this way, now another. But we are not now a body, now a mind; we—the same we—are both at once. Does it take an observer—philosopher or Judeo-Christian God—to split the attributes apart? Is it perception that does it? I want to draw an analogy to the electron as wave-particle—which is merely the scientist’s natural appeal to the duck-rabbit. So then why don’t the modes of extension and modes of thought pair off? Is it because the concept-structures under one attribute and another are not isomorphic? Need they be? I think Spinoza misleads us when he says, “the order and connection of ideas is the same as the order and connection of things” (Ethica II.7; italics mine) because ideas (that is, the ideas of things) are only a subset of his modes of thought. Are there really modes which lie outside? Yes, the affects. What about modes of rational thought? I hear the early Wittgenstein saying no. Spinoza does not give a straight answer, but no would create a biased affinity between reason and extension which should not follow from his postulates.

Let me add here that Spinoza’s comment on the errant tongue must be paradoxical because he is clear about there being an idea corresponding to every physical thing, which, as the body is moved, is perceived. So considered under thought, the errant tongue is not a lack of idea, but merely an idea which is confused, or unconnected to reason. The comment itself must be a slip. In such slips should we steal Curley’s phrase and call Spinoza a dualist despite himself? I think we have slipped now and then into reading Spinoza as Descartes—indeed Curley himself points out that our language is so dualistic in practice that in common speech we end up explicating Spinoza in terms of Descartes’ ontology.

∗ ∗ ∗

English law conditions us to consider murder a complement of act and mind. If act and mind—extension and thought—are merely ways of seeing the same thing, then some ways of seeing must be partially blind, because as physical phenomena the act of Nero and the act of Orestes were the same. The concept-structures under this attribute and that are not mutually spanning. (Or must we consider the firing of neurons; vibratory modes of the pineal gland—however you’ll have it—as part of the extended world, then the two murders become distinct? I don’t think so.) Considered under thought, Nero was clearly in the clutches of his affects—of the fear of death, the lust for power—whereas if we listen to Orestes, we hear reason and the affects wrestling:

I grieve for what I have done. I see no end. I am a charioteer colliding with another. Beaten from the track, I wander far from my course. Friends, my mind and senses crash together. Listen! I feel my heart pounding like a boxer's weighted fist on my ribs. Always the beat is rising, as if I led the singers in the dance of anger through Argos to their deaths. No, wait! My mind is still whole. I declare publicly: I was right to kill my Mother. Agamemnon's blood was on her hands.

(out of Robert Lowell’s loose translation)

In part IV of the Ethics Spinoza notes that the judge who sentences the guilty man to death is guided only by reason. It would be wildly disingenuous to cast Orestes as the dispassionate judge, but perhaps his reason and his passions have coincided in purpose. Indeed Spinoza tells us that the free man might be guided to the affects by reason; reason guides us to the pleasures of green plants. Between pleasure and not-pleasure why should we not choose pleasure? The point is to let reason and not the pleasure itself be our guide.

∗ ∗ ∗

What is a law of nature if one phenomenon can be explained by these laws under one attribute; those laws under another? Does Spinoza consider Orestes’ revenge as necessary as that Clytemnestra’s blood should fall and scatter and glow crimson? Is the principle of self-preservation as fundamental as that of least action? And need one set of laws be isomorphic to the other? Their conclusions must be the same. One set can hardly be clockwork if the other is capricious. (Conclusions, that is, where they exist; some questions under some attributes must be unknowable.) If thought is merely another way of seeing the physical world, where extended things patently obey deterministic equations of motion—why, we should need a Newtonian ethics, which trickles down from the universals like geometry.

Could this be the motivation for Spinoza’s project? In his essay on the improvement of the intellect, Spinoza espouses a basically cumulative view of the history of thought: our philosophies are hammers with which better hammers are made. There is no ideal hammer which might exist on Earth, no dusk when the blacksmiths might go home for good. Old hammers rust and, yes, crumble. Thus in his maturity perhaps Spinoza belies the prophetic tone of his Ethics. It is unclear whether for Spinoza the doctrine of one substance became just another provisional almost; in our far-from-cumulative history it seems it was never polished again. If the glass-dust had not stopped his body being moved in a great many ways, I wonder what more perfect hammer Spinoza would have made of it.

MMH: The trap of affect, for Spinoza, is not so much letting the stream of determinism sweep you along but is rather struggling against it, resenting the inevitable. If there's nothing in your future to disturb a constant bounty of green plants and good food, revelling in those pleasures is not a problem, but developing a green-plant addiction when reason tells you that you'll soon be in the desert is to surrender yourself to immoderate passions. Reason for Spinoza seems to have a lot to do with foresight, with recognising necessity as such and not letting it sneak up on you as passion. Had Nero not been so fearful and so jealous, it seems, Spinoza would forgive him his matricide as a fact of causation. Had Nero aligned his reason with the irrefutable logic of particles and their solemn knocking-together he could have redeemed his crime. By the same token, the virtuous criminal from the Blyenbergh letter is virtuous insofar as he has reasonably assessed his nature, and pursues his crimes because they serve him well. The sudden stop in Orestes' mental turmoil could not be a better Spinozist rallying cry - ‘No wait! My mind is still whole.’ But this mental unity is not inevitable, it depends upon indeterminate machinations of thought ('God was not the cause of this, but was the cause of Nero's act and intention'). Clytemnestra and Agrippina’s deaths were perfect necessities, but their sons’ justifications and wills were not beholden to a parallel set of laws. Reason discovers causation and the affects are beholden to it, but what is the structure of the thought or will which lets us strive towards reason, can this power too be reason itself?

The special affinity between reason and extension can be found in Spinoza’s postulates, I think, but not without muscling out the body. Reason must make its way back to the world, but by disciplining the senses and their predilection for affects. Adequate ideas are causal phenomena, they are adequate precisely in that they are sufficiently clear and whole to have caused things in the world to occur. Where the intellect fails to understand causation, affect creeps in to explain the work of determinism. I think that in all his talk of affirming the world of necessity, there is something of the Newtonian ethics you speak of at work. Not, however, because events under the attribute of thought are already subject to the same necessity as events of extension - there seems to be room still for caprice in thought - but because, if we are to heed the example of Nero and Orestes, our power over thought should be employed to align the will with the necessary. We get a picture of events in matter, which must be accounted for in chains of mental causation, but wherein we have some power to shape the links between inevitable extensive occurrences. With this shaping, we make ourselves either powerful or weak.

It is fitting that, legally speaking, passion should be considered a mitigating factor: an excuse. As far as Spinoza is concerned, Nero's knavery is not the mere fact of his passion - we are agreed that Orestes shares this - but its function as a kind of excuse. Necessity is not an excuse for the powerful - and, by extension, the virtuous - man2. For Orestes, that he could not do otherwise expresses that he acted virtuously and willed his matricide, for Nero, the inability to act otherwise is not matched by an adequate will. The lust for power, and this neatly distinguishes Spinoza from Nietzsche, is precisely the opposite of power. Poppaea's taunts are self-fulfilling, Nero is 'a child controlled by another' (Tacitus, History Book 14 Chapter 1) insofar as his thought is an inadequate cause of his own actions. Again, however, it seems that some second-order variety of thinking rears its head. Under what attribute should we be listening to Spinoza? Is it in some compartment of rational thought that Spinoza’s own will to power resides, or is it a kind of passion which spurs us to be powerful rather than weak? If it may agree with one’s nature to be criminal, might it agree with one’s nature to be causally weak?

Spinoza's identification with a cumulative philosophical tradition is intriguing, both in that it puts distance between him and the Cartesian glare which risks overpowering the Ethics, and in that it draws Spinoza closer to Hegel, from whom he is forcibly separated by Deleuze's book. We might well imagine a philosophical hammer that does the job of the unity of substance, by rejecting certain dualistic illusions and using real rather than hypothetical subjects as its viewpoint, without the pitfalls of Spinoza’s contradictory monism. We can, perhaps, pick through the rubble of a bold cathedral, or look at an inaccurate picture of a flea, and discern one or several directions of movement: flights and pursuits we can follow more cautiously. Then again, lenses and hammers do not mix well. One is brittle, the other ductile. It becomes difficult to see how to reform Spinoza’s system without starting anew; there is a fragility in a system of such obsessive interdependence which does not suffer reforging well. In the hands of anyone but poor, silicosis-stricken Spinoza, could – and should – such a reforging be anything more than Deleuze’s monstrous conception.

CH: Why must Clytemnestra die? Is the sacrifice of Iphigenia to be considered sufficient reason under the attribute of poetic justice? To the old poets that curse on the house of Atreus was as good as a law of nature.

If some things are unknowable under some attribute, then actions can come out of the aether under that attribute, because there exists no concept to fit to their cause. Reason discovers causation—where? In the axioms to Part I, Spinoza asserts a principle of sufficient reason. He also ties up knowledge inextricably with causation:

The knowledge of an effect depends on, and involves, the knowledge of its cause.

(Ethica IA4)

It would seem determinism is a universal property of his one substance. But under what attributes does the world follow a deterministic law? Extension, yes, and thought only insofar as it is guided by reason. Thus perhaps the affinity between the extended world and rational thought, and the reason why the affects, insofar as they are ideas, are necessarily confused. But why must determinism under extension reflect a more fundamental determinism—and on what basis of experience does Spinoza presuppose one? Perhaps it is my own inattentiveness that causes me to read in Spinoza an inkling of the Kantian idea that causation is only a property of what Spinoza would call the extended world—something inherent in the attribute, not the substance. For it is indeed possible that determinism might arise in one way of seeing a non-deterministic substance: attend to the real physical world understood through Newtonian dynamics.

The attributes—ways of seeing—are lenses through which me might see—almost see; incompletely—truths about the universal One. The fundamental law of nature is not something we can examine straight-on, but it’s something we might still give a name, and I think the true law of nature in Spinoza is what he calls conatus. (The other good candidate must be sufficient reason itself.) The conatus—that property of things to strive for their own preservation—is all-pervading and, after a little reflection, necessarily mystical. It takes little transfiguration to become Schopenhauer’s Wille. The conatus is a will to life, and insofar as it causes us to seek reason, a sort of will to power.

A will to what kind of power? It is indeed a power, so-called, which comes in resigning oneself to the torrents of determinism; following the clockwork dictates of the reasoning mind whose ideas follow the order and connection of extended things. If not ‘causal weakness’, then at least receptivity. (We begin to make sense of Schopenhauer’s strange reflection that Spinoza’s spiritual home was on the banks of the Ganges.) Perhaps the idea is that without determinism, we couldn’t determine anything either. But the whole thing strikes me—as it struck Schopenhauer—as palpable sophism. What about death, when the conatus comes at loggerheads with the inevitable? Surely then the conatus-made-reason dictates that we rage rage, against the dying of the light? It is in my nature that I should strive to live, but under a different attribute it is in my nature too that I should have a finite duration. In this regard Spinoza’s argument against suicide seems weak. If I might rage against one aspect of my nature, why not another? It is slipped in by the axiomatic back-door that we must take joy in meditating clearly on the all-absorbing conatus. Why not, as Schopenhauer does, see it as a curse? Why not lose one’s grip on the necessity of cause and effect, and drown in the very passion of the tide? (At this point I’m paraphrasing Isolde, whose reading of Schopenhauer was as good as anyone’s.)

It would do us well to attend to what exactly is slipped in by means of the axioms. Beyond conatus there are fragments of real physical law—the law of reflection at equal angles, for example—though Newton’s first is taken, bizarrely, to be self-evident. (Bizarrely because the Aristotelean dynamics follows just as readily from an interpretation of sufficient reason.) Schopenhauer’s own philosophy must surely be considered a cumulative refinement of Spinoza’s doctrine of the One—but for him the geometric method is a crutch for sound legs. He throws away the scaffolding and retains only the truth of the edifice of propositions therein. It is well known that the laws of logic are not useful for deduction in practice; only to check that a demonstration is free from error. One can imagine a sort of demon to the geometer who attempts to negate the conclusions by as subtle as possible changes to the axioms. I think this demon would have an easy time with Spinoza; I think his axioms are fine-tuned. If all the truths of his system are actually inherent in those axioms—and the path of the Ethics a simple case of fleshing-out—then what is Spinoza’s actual condition for truth? Experience? What kind of experience?

By what is Spinoza really driven to call slavery that wild donjuanist agency of Nero and Poppaea in Monteverdi’s haunting duet? To call slavery indeed the power over men? Surely Orestes’ power too comes not in his reason but his rage against the curse—if we put the propositions to one side and make brief contact with our common sense? Orestes who is hounded by the spirits of determinism (as I might not too unfaithfully read the Furies) while being determinism’s agent all the while? I fear there is a death-urge lurking behind the enigmatic life of the mind from Part V. The death-urge which is after all in the late Freud what makes us deny the body. If reason is life, then are the passions death? Has Spinoza married Eros and Thanatos centuries before Wagner?

When Wagner read the World as Will, he felt the need—his memoirs tell us—to give rapturous expression to his state of mind, which eventually came in the form of a certain stage-play. I have been trying to get my head around—and indeed to experience—the state of mind to which Spinoza alludes in Part V—that joyous meditation on life itself permeated by the intellectual love of God; that happiest day in the life of the mind; that passionate embrace of the inevitable. [Here again Nietzsche and the Dutchman begin to coalesce.] What is the anti-Tristan which might give that mood expression—the art which doesn’t seek and find escape from causation, but thrives on it? Or is it one entirely at odds with rapturous overflow? Is the Ethics itself precisely the artefact I seek? Rapturously express, if you will.

MMH: I worry that we mislead ourselves if we think of the attributes as merely ways of seeing something. To be sure, the attributes are lenses of a kind: look through one and all the particles of the world pattern themselves in the shape of objects, peer down the scope of another and we see Nero’s paranoia, and Orestes’ fatal reason. The problem comes, or so says the phenomenologist, when we start assuming, explicitly or otherwise, that there exists a view from nowhere, substance known without a lens. Spinoza certainly speaks at times as if some mystical cavity in God contains things apart from their appearance under attributes: ‘a circle existing in nature, and the idea of a circle existing, which is also in God, are one and the same thing displayed through different attributes’ (from Ethica II.7N), but this reading leaves us wondering what a circle is outside thought and extension. The circle in nature and the circle in the mind might well be in some way identical, but they are not one prior thing under two different microscopes. If God is the unity of his attributes, doesn’t substance reveal itself as a constellation of lenses surrounding a cloud of dust, which – for the purposes of all possible observers – is only ever visible through a looking glass? Eyes have lenses too, of course, but when we speak of seeing the ‘real physical’ world through Newtonian dynamics, we imply the priority of an immediate perception, gazed upon through the secondary – explanatory – lens of a theory of causation. The relation of attributes to substance seems rather more entangled than that of explanation to sense-data, the attribute of extension, with its determinism, contains in whole the external world as we find it.

It seems that while the realm of extension is walking properly at God’s heel, and proceeds without fault from his nature, the world of thought relates to extension asymmetrically, always matching its strides but sometimes deviating with its affects.

Hence God's power of thinking is equal to his realized power of action—that is, whatsoever follows from the infinite nature of God in the world of extension (formaliter), follows without exception in the same order and connection from the idea of God in the world of thought (objective).

(Ethica II.7C)

One presumes therefore that insofar as the conatus is a rational drive, and thus one that finds an extensive correlate, it cannot – for Spinoza – outpace the mortality of the body and yearn to defy the necessity of death. Something quite drab sounding which you touch on when you say you strive to live under one attribute and must die under another is that we aren’t quite sure how many attributes God has – is God the One which unifies only thought and extension? It seems a disagreement between rational will and rational world is impossible for Spinoza – the conatus cannot be that Schopenhauerian will which goes on and on in spite of the natural decomposition of our internal relations. Or rather – in contradiction with the corollary above – it does, but in a strange and stranded space of eternity:

The mind can only imagine anything, or remember what is past, while the body endures.

Nevertheless in God there is necessarily an idea, which expresses the essence of this or that human body under the form of eternity.

The human mind cannot be absolutely destroyed with the body, but there remains of it something which is eternal.

(Ethica V.21-23)

Is the will to self-preservation excised in this solely mental persistence? Or does it go on longing for the preservation of a body which is destroyed? What is this poor, lonely mind – which cannot imagine or remember – up to?

I agree that the case against suicide is weak, indeed it seems to be circular. We shouldn’t kill ourselves because that would decompose the relations which are our essence amounts to nothing more than ‘we should preserve ourselves so that we are preserved’. Even the ‘should’ is redundant, the Ethics is clear enough that there is no volition in the physical machinations of suicide. The question again is a why which presses on the axiomatic: why is a given cluster of relations a good worthy of preserving? Why indeed pay attention to cause and effect if affect offers the only course which looks something like freedom; and at worst is slavery. Slavery to what? To the goings on under extension. Those same goings on, we presume, to which we are chained by reason, albeit with less rapturous consequences in the mind.

Striving to know the geometry of God and his effects is the process of clearing confused ideas out and finding clear ones in their place. Passion, as V. 18 (‘No one can hate God’) and its note are keen to emphasise, is always a consequence of confusion. One imagines that in light of this rapturous expression would find little space in the committed Spinozist’s meditation. Schopenhauer, and certainly Tristan, was in little doubt as to whether he could hate God. But the Ethics is still a little too rapturous, I think. Why love God, if even the coolest intellectual love betrays a misguided amazement at necessity? Spinoza tells us in this note that we cannot reasonably hate god because he is the cause of pain (this is to let passion creep in) so it may hardly be countered that we should love God because he is the wellspring of pleasure. Spinoza loves the clarity of his labyrinth and marvels at its ability to pack up into a little travel-box of axioms, feathered and gilded with all the care of a miniature in a locket. There sits Spinoza, hands scrubbed of every trace of grease, turning over a new-ground lens in his hands. Looking at it, not through it.

CH: Let us briefly ground ourselves—as can be comforting—in definitions.

By substance I understand what is in itself and is conceived through itself, that is, that whose concept does not require the concept of another thing, from which it must be formed.

By attribute I understand what the intellect perceives of a substance, as constituting its essence.

By God I understand a being absolutely infinite, that is, a substance consisting of an infinity of attributes, of which each one expresses an eternal and infinite essence.

(Ethica 1D3;4;6)

On the one hand, substance is unambiguously the thing-in-itself. It comes prior to its perception or conception—and indeed the attributes are nothing more than ways the substance—undeniably a something—is conceived. So with anything whose very existence follows a priori. For Spinoza (and whether I agree is muddy and probably tangential) the impossibility of the all-seeing perspective-from-without does not rule out the possibility of the thing-in-itself. All realizable lenses are imperfect; God’s omniscience is the totality of perspectives-from-within. In this regard it baffles me how a substance can consist of attributes; thus for substantiam constantem infinitis attributis I really want to read a consistent substance with infinite attributes. Yes, one defies the major translators at one’s peril. On the other hand, we can’t forget that the only substance which can be conceived without contradiction is God, and God has infinitely many attributes, one of which is intellect. So God’s infinite intellect, which is at least partially identifiable with the Subject (the Subject insofar as it is rational?) comes promptly with the thing-in-itself it might perceive. God perceives himself; God conceives himself. Not only that, God loves himself.

Spinoza talks of an infinity of attributes, yet attends only to two. What gives? I think Newtonian Dynamics is properly considered as an attribute; an attribute might well be an intellectual superstructure on some more primitive other like sense-perception. The attribute I want to know about—if Spinoza considers it an attribute at all—is time. Causality presupposes time. Sufficient reason presupposes time; I want to say (though I can’t prove it) that will—conatus—presupposes time too. Can we really let duration and extension sit side by side as analogues? To my mind, perfect determinism robs time of its proper status as a parameter and makes it as good as another dimension. One can imagine—this is the sort of thing Laplace’s demon would find exceedingly funny—the world stretched out into a fourth dimension, quadruply infinite, crystallized, static. Excuse my perspective not only from nowhere but from no-when too. Is this what Spinoza means by eternity? And is his conatus really a will to stasis? The truly static, in death, persists forever. The philosopher in meditation sits perfectly at rest. Perhaps the reverie of Part V evokes this (unrealizable, hypothetical) perspective from outside time, where the world is whole and still and determinism and its effects are laid out as patent fact. Or perhaps it evokes a longing for the limiting far-future (another cancellation or collapsing of time) where even clockwork physics teaches us that the world will peter out. Is the second of thermodynamics the clearest manifestation of conatus in what we call physical law? Schopenhauer’s Wille, on the contrary, is eternally restless—yet Tristan, without denying his nature as a romantic hero, is able to will the Wille away.

Is time just a way of conceiving a thing-in-itself which does not presuppose duration? If so, the experience of time is deeply illusory (and if we file Spinoza with the old Eastern mystics this is a doctrine we might not quite put past him). Spinoza teaches very little about the nature of experience; through his attribute of thought I feel I see only the thoughts of other men. This is almost a paradox in a philosophy so superficially introspective. Indeed in ethical matters too Spinoza reads as outward description, almost sociology. This is presumably his defence of the position on suicide: there is no assertion that we oughtn’t kill ourselves—merely an observation that the phenomenon of suicide is against the human nature and an ultimate expression of impotence. As you say the should and should not are annulled by determination. Watch civilisation and see the good and the bad—pragmatic by definition—come and go. Sin is behovely—and indeed the suicides of history couldn’t have been any other way.

Not that lonely mind but that lonely idea—for mind is but the thought-correlate of the physical body, which following its order and connection decomposes as the body does. I want to say the extensive correlate of the rational conatus is simply perpetuation—so ceasing-to-be quietens too the will. Or is there conatus in the idea itself? There are ideas of ideas, and there is conatus in everything. See how soon after Descartes—for whom they languished on the lowest rung of ontology as merely modes of thought—ideas are once again mystic and transcendental. The mind itself is an idea, albeit one of a different kind. So yes, ideas strive. They needn’t, for see, they are already eternal.

MMH: Surely God does not perceive himself apart from his attributes. The attributes seem to each allow for some kind of perception, but a perception limited to the scope of the attribute itself. Under thought, we see the idea of the circle and not the circle of extension. God, even if he is the thing-in-itself, is surely never encountering himself as such. Substance is conceived through itself, but – whether its attributes are things which compose it or things which it has – is this conception not already under the attribute of thought?

As for time, the beauty of a clear labyrinth is that one need not walk through it to see its twists and dead ends. It is all there in crystal, stretching in space but not in duration, showing without a step the inevitable, pre-calculated logic of our passing through it. Time, or more pressingly the causation you rightly associate with it, becomes an architectural phenomenon, events under extension are structurally bound to other events which are, for all purposes, simultaneous with them – no more or less necessary than the first conditions of the universe. Causation is merely the law which says that under extension the pattern of events should crystallize outwards. Yet at every still point in that empty hourglass there sits a mind, which is in part in motion. Those infinitely many minds either sink into the clarity of the static maze, and look as far as their reason’s sight will let them, out over the stretch of simultaneous time. Or those minds may choose unreason, wallow in their view from somewhere, and feel time as an indeterminate passage. Why should we choose to see already around every corner of the labyrinth? Why not, as our only choice, bemoan and celebrate every new present as a miraculous contingency?

I think you may be right, in any case, that asking Spinoza why we ‘should’ do or think things is misguided, insofar as the Ethics as at its core a descriptive philosophy. Deleuze refers to it repeatedly as a kind of ethology, a study of the kinds of capacities for affect which humans have, and a study of the kinds of thinking which are poison or food to the organism that thinks them. The indeterminacy of our meta-thought – that second reason which chooses to be reasonable rather than passionate – keeps the spectre of the prescriptive at the corners of our vision, but even here Spinoza seems indifferent to the ethical proper. It might be poisonous to the mind to be blown about by affects, insofar as Spinoza defines the healthy mind as a rational thing: a web of relations which unreason decomposes, but we cannot choose our essences, nor sway our extensive behaviour. A detail which still troubles me is the relation of mental states to actions. If it is physically determined that a person should commit suicide, is a corresponding state of despair determined in lockstep with it? It is one thing for reason to match the occurrences under extension insofar as it predicts them, identifies cause and effect, but there the mind is playing catch up to the world of extension. When Spinoza concedes to Blyenbergh that God was the cause of Nero’s ‘act and intention’, what is his intention in contradistinction to his ungratefulness and lack of compassion? Does Spinoza suggest that the will to matricide would have sprung upon Nero quite out of nowhere, if he had reigned in the passions and ignored Poppaea’s taunts?

Perhaps conatus is not so much the will to stasis as the will to self-dissolution, an instantaneous romp through successive, but simultaneous, instances of the reasoning mind. The conatus seems to me a will which refuses to become trapped in any given affective moment by keeping in sight the eternal fixity and that which has come before and will come after. Perhaps Schopenhauer could get behind the conatus after all, insofar as it is a negative will, the will away from all that willing that would destroy us. It is little wonder that the Ethics’ strongest commendation of any activity is of Part V’s loving contemplation. The contemplation is not a prayer, or an act of devotion, but a reaching – or rather a realization – of stasis. We can imagine that the philosopher at rest in this reasoned love has stopped experiencing duration altogether. There is no surprise to trouble the philosopher with a clear view over time itself. Here sits Laplace’s demon glued to the television screen, feeling a moderate love for the chains he can see stretching below an ample horizon.

How should we reconcile this life of the mind (and the mind alone) with: ‘He, who possesses a body capable of the greatest number of activities, possesses a mind whereof the greatest part is eternal.’ (Ethica, V.39)? Is reflection or bodily busyness the way to eternity? The body and its activities play a curiously hypothetical role here. It is by striving under thought that we increase the body’s capacity for activity (by brushing off the affects) and it is eventually the mind which is, in part, made eternal. For all its presence in the last propositions of the Ethics, the body may be bypassed; it is after all its capacity and not its actions which are vital. The conatus brings us by a strange route to self-dissolution, it wards off poisonous affects and in doing so increases the power of the body (where power should not be confused with freedom). At the same time, the mind anchored to this body is cleansed of distractions and lusts and here

it will come to pass that (V. xv.) he will be affected with love towards God, which (V. xvi.) must occupy or constitute the chief part of the mind; therefore (V. xxxiii.), such a man will possess a mind whereof the chief part is eternal.

(from Ethica V.39P)

Those who have, in life, dissolved themselves into the undifferentiated substance of God, ‘should scarcely fear death.’ (from Ethica, V.39N)

CH:

Further conceive, I beg, that a stone, while continuing in motion, should be capable of thinking and knowing, that it is endeavouring, as far as it can, to continue to move. Such a stone, being conscious merely of its own endeavour and not at all indifferent, would believe itself to be completely free, and would think that it continued in motion solely because of its own wish. This is that human freedom, which all boast that they possess, and which consists solely in the fact, that men are conscious of their own desire, but are ignorant of the causes whereby that desire has been determined.

(from Epist. 62 to G. H. Schuller)

It seems there are two ways of reading the attribute of thought. Both, I think, rely on the notion that thoughts correspond to physical motions of the body, so I take back my previous suggestion and include neurons firmly in the extended world. In the first reading, where we take Spinoza’s definition of attribute as written, ideas are the forms of things which exist regardless of being perceived/conceived (here the two are the same) by the intellect. Attributes are different ways the intellect conceives the world. Thus we have the thought which is not conceived; the thought that is really the thoughts of other men. But note that the intellect here, the Subject, is really something other to the world. It is one thing for ideas to exist, and another for them to be experienced—and the mind’s—my mind’s—ideas are the Subject’s direct object. This reading is dualistic, and perhaps Spinoza’s insight here is the that Subject—the soul; the seat of experience—merely watches on, under the compelling illusion of agency, with no power to affect the world. It watches on does and absolutely nothing else: it cannot reason, cannot form memories; these both have their correlates in the brain. And the intent to murder is really the observation that my body is about to murder, or is thus prone.

However, what if we take ideas as necessarily experienced things—that is, in Spinoza’s monism we see the doctrine that the extended world and my experience of it are the same thing? In this reading consciousness is not something external and mysteriously absent from the philosopher’s exposition, but is the very attribute of thought—but note that we must then discard Part I’s definition of attribute as an imprecise vestige of Descartes. To form an idea is to experience, and I experience clear thought when my body’s parts (neurons and all) are in disciplined order. To save Spinoza as a radical monist we must take this second reading—or somehow marry it to the first if we want in him a radical, consistent monist. I can’t decide whether this view is essentially solipsistic, in that my experience of the apple corresponds not to whatever neuron has been touched by the apple, but to the apple. So where’s the room for your experience of the apple? How can my apple be confused if yours is clear and distinct? Do we have an attribute each? But how many of these distinct attributes are there—each corresponding to a subject? Why do I get one and the stone not? I want to say: because there is only one; it is I.

Perhaps the way out of these issues is to consider God’s intellect, of which your intellect and mine are parts. Our experiences are not distinct attributes but slices through the unified whole experience in God. Where does yours end and mine begin—well, where does your body end and mine begin—and an idea might no more readily slip from my mind to yours as my arm become mysteriously conjoined to your torso. The problem, of course, is that now the stone experiences too; my experience is richer than the stone’s because my body involves a more complex interplay of internal parts—it is more capable. (What about the experience of a Persian rug? What about the experience of my decaying parts—does their experience only wane as I decompose?) Spinoza writes if the stone were capable of thought—as if it weren’t—but maybe that’s a slip back into the old Cartesian terms. Put it properly and it sounds like Buddhism again.

We’re now in a position to understand Nero, attending to the start of that same proof:

He who has a body capable of doing a great many things is least troubled by evil affects (by IVP38), that is (by IVP30), by affects contrary to our nature. So (by P10) he has a power of ordering and connecting the affections of his body according to the order of the intellect, and consequently (by P14), of bringing it about that all the affections of the body are related to the idea of God.

(from Ethica V.39P)

It’s unclear whether Spinoza’s intent is merely to distinguish man from infant and animal, or to distinguish this man from that; the talented from the coarse, the weak from the strong. All the same, the point of developing the body’s capacity is to fend off external causes. Nero’s knavery was a lack of discipline; a lack of order in his body (and so in his mind) which made him so susceptible to whatever passing cause effected his act and intent. That cause was trivial and wholly extrinsic to him—in a word, was God. His undiscipline, however, was a lifetime in the making, and those revealed qualities—ungratefulness, disobedience—were its manifestations. Discipline, it seems, is less about making one’s mind like God than about letting God in: that man the greatest part of whose mind is eternal, he has not made immortal what was there before, but replaced his confused notions with ideas which have existed eternally. God permeates the mind of the philosopher. The more infinities come in our conception, the more we express God’s essence.

Spinoza disdains undiscipline, and this can hardly been seen as an ethical proposition. His answer, as ever, is that it’s simply in our nature to fortify ourselves against those slings and arrows which every moment might make us deny our nature. (And here we revel in the Dane’s infinite irony that his armament against fate is really an armament against himself. The world and my experience of it are the same thing.) The excitation of the mind entails the excitation of the body, vice versa, and every thought might be a lethal one. Thus we might see in conatus a will to quieten that thrumming in the world which constantly excites us to thought. It is perhaps a kind of insomnia. To die—to sleep; no more. And once again the conatus has turned round, by sophism or necessity, and become a will to death.

1 Alain de Botton did: one doesn’t easily forget how Spinoza was the unfortunate subject of his attempt to produce philosophical internet porn. [Back to text]

2 Ethica IV.20 and proof: ‘The more every man endeavours, and is able to seek what is useful to him—in other words, to preserve his own being—the more is he endowed with virtue; on the contrary, in proportion as a man neglects to seek what is useful to him, that is, to preserve his own being, he is wanting in power.’; ‘Virtue is human power’ [Back to text]